Adora Shortridge is a Masters of Arts in the School of Sustainability conducting a research project on urban heat islands and how to prepare schools for it. The Urban Heat Island Effect has affected public health, safety, climate change, weather, and many other environmental issues. Adora seeks to solve these issues by understanding its effects on schools.

“As cities continuously morph and grow, it becomes more critical to design our communities to be resilient, diverse and inclusive, more livable, and natural. Educating all levels of the public and stakeholders is crucial to the effectiveness of strategies mentioned above, as well as to the future of our soon-to-be sweltering cities.”

Read more from Shortridge in her Q&A.

Sustainability Connect Question (SC): Tell us about yourself and your passions in sustainability.

Adora Shortridge (AS): My name is Adora Shortridge. I am from a small town in Nevada, earned my Bachelor’s of Science in Environmental Science, and I enjoy reading, yoga, DIY projects, all things outdoor recreation, and adventure. I am halfway through my Master of Arts in Sustainability, of which I am focusing on heat readiness in elementary schools. My passions in sustainability include, but are not limited to, human-environment relationships, climate change communication, urban heat, environmental racism, and holistic paradigms.

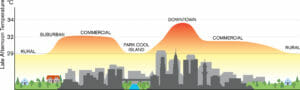

SC: What is the Urban Heat Island Effect (UHI) and how can we solve the challenges associated with it?

AS: The Urban Heat Island (UHI) occurs when a city experiences much warmer temperatures than rural areas due to how well surfaces in each environment absorb and hold heat. Dark and impervious surfaces like asphalt, steel, and concrete combined with a major reduction in vegetation coverage cause city temperatures to rise. On both a small and large scale, we can tackle UHI challenges by adaptation, mitigation, education, and smart growth. There are many adaptation and mitigation techniques unique to various climates, but increasing tree/vegetation cover, using cool and permeable pavements, creating cool and green roofs, and most importantly, utilizing smart growth design. As cities continuously morph and grow, it becomes more critical to design our communities to be resilient, diverse and inclusive, more livable, and natural. Educating all levels of the public and stakeholders is crucial to the effectiveness of strategies mentioned above, as well as to the future of our soon-to-be sweltering cities.

SC: What does your research entail and what drove you to start this project?

AS: I was separately involved and very passionate about two fields; education access and environmental justice. When entering graduate school, I was seeking a project that could overlap my deep values I had cultivated from my background. In high school and undergrad, I was very involved in Academic Opportunity Support Programs (AOSP) for first generation students, which is where my drive for inclusive, equitable, & affordable access to education originated. In undergrad, I began a research project through the McNair Scholars Program that involved extreme urban heat, where I learned about the historical environmental injustices of vulnerable populations in urban areas. My research project now focuses on heat readiness–how prepared a community is for extreme heat or heat waves within elementary schools in South Phoenix, an area that has historically faced environmental injustices. The elementary schools in my study host one of the most vulnerable populations to extreme heat, and in this case, low-income and mainly students of color. I aim to understand how school staff perceive and respond to schoolyard heat and what components make up a “Heat-Ready School,” meaning those that are increasingly able to identify, prepare for, mitigate, track, and respond to the negative impacts of schoolyard heat. My research entails semi-structured interviews and an anonymous panel of experts (the Delphi method) to create an “HeatReady Schools” evaluation and guidance toolbox.

What are the social and health impacts of UHI and who should cities be working with to solve it?

AS: UHI research has identified “intra-urban” heat islands, areas within a city that are hotter than others because of the uneven distribution of heat-absorbing materials and green spaces. These result in disparities in the way that communities are planned, developed, and maintained. Socially, the impacts of UHI are disproportionately higher for people of color and low-income households. Populations that bear the brunt of heat-related health impacts include: older adults (65+), outdoor workers, those with existing medical conditions, children/infants, pregnant women, athletes, those who live alone or who are homeless, and those with limited personal resources (i.e. income) to deal with extreme heat. Health concerns include impaired water quality and heated stormwater runoff, human thermal discomfort, impaired [human cognitive] abilities to focus, heat exhaustion and illness, heat stroke, heat-related mortality, increased energy consumption which elevates air pollutant emissions and can exacerbate respiratory difficulties. Especially during summer, everyone is at higher risk for experiencing heat-related issues if air conditioning units suddenly break and repair companies struggle to keep up with demand. Cities should be working with: energy utility companies on their policies during peak hours/periods; the transportation sector for improved spatial connectivity and emissions regulations; hospitals to track, understand, and prevent heat-related illnesses/mortalities; local businesses/restaurants/services to provide cooling relief stations; local residents in high risk zones; the homeless population and shelters; and school policymakers to better educate, collaborate with, respond to, and protect our communities from UHI impacts.

SC: What are your biggest learning outcomes?

AS: My biggest learning outcomes include improving education access and communication strategies regarding climate change impacts in urban areas, enhancing the connectivity of resources and access to public transportation and relief networks, and inspiring more people to collaborate across fields and disciplines. On a more personal level though, my goals are to establish multi-scalar connections between people of similar goals, values, and visions with resources. I strive to reduce the amount of polarization in our society’s media, communication, policies, planning, and developmental aide efforts. Though a large task to tackle by one person, by collaborating and combining efforts already undertaken, we can focus on a more holistic, inclusive, and sustainable future for all living on our planet.