In this series, we’re sitting down with the Swette Center affiliated faculty to catch up on food systems, innovation, and what makes a good meal. See the rest of the series on our Food Systems Profiles page.

Read on for an interview with Dr. Joni Adamson, President’s Professor, Environmental Humanities, Department of English, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, & Distinguished Global Futures Scholar, GFL.

How did you get interested in food systems issues?

When I first started teaching environmental literary criticism in the early 2000’s, I was helping to innovate a new field. The field of environmental humanities didn’t yet exist, but after the 2000s, humanists in environmental history, philosophy, ethnic studies, etc., began banding together with us to grow this new field exponentially. Now I teach environmental humanities and there are tens of thousands of people working in this field around the world.

Without realizing it, in my earliest teaching days, I was taking a “gloom and doom” perspective on environmental issues. I could see students pulling away from me and not wanting to talk about the “doomed” future that they were facing. Then I read a wonderful short story by Scott Russell Sanders, a well-known environmental writer, that talked about a lesson he learned from his teenage son. His son was becoming a little rebellious and surly, and Scott was confused by his actions and attitude. He decided to take his son on a white water rafting trip and he noticed how incredibly happy his son was on the boat, leaning into the waves, breathing deeply as he handled his oars, and admiring the beauty around him. He asked his son later during the trip why he always seemed so angry with him, and his son said it was because he ruined everything by constantly having a gloom and doom outlook on the world. After reading this story, I realized the main message immediately. When you teach any type of environmental issue, you have to teach it with hope. Then I realized about 10 years ago that you could teach all the environmental issues surrounding food without ever talking about gloom and doom because you can also discuss how we might move towards regenerative practices and more sustainable food systems. Now, my students often leave the classroom feeling like they can do something about food system environmental issues by changing their diet. By helping my students feel engaged with the role they have to play in the food system, they usually feel hopeful about the future.

Share a glimpse of your current research and how it applies to food systems transformation.

I’m researching “syndemic” or synchronous pandemics, and the ways that food system vulnerabilities exacerbate risk among historically colonized/oppressed/marginalized peoples. During 2020, most of us were wearing masks and staying home to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Synchronously, George Floyd was murdered that year, calling attention to other Black men and women lost to racism and violent policing. This revealed how so many different issues are linked by colonial histories, imperialism, racist infrastructure, rogue law enforcement, and the deaths of too many black lives. The concept of syndemic was already being used to talk about climate change, diabetes, and food insecurity. My Food Justice Research group and I are linking this concept of syndemic to the food system because the populations that are most food insecure have a higher risk for COVID-19. These are synchronous pandemics: food insecurity, racism, and COVID-19. What my team and I are looking at is how we can activate humanists to become communities of purpose. Humanities is a field in which scholars usually have an interest, whether it be literature, history, philosophy, etc. We don’t want to only be experts in our interests though. We want to be a community of purpose. Becoming a community of purpose requires us to work with colleagues across the disciplines to create educational opportunities that hopefully teach students how to be a community of purpose, and not just a community of interest. We want to forge a community of purpose that makes us the leaders we need to confront syndemics.

What’s an innovation in the food systems world that you’re excited about?

I’m really excited about the Swette Center and ASU’s role in influencing the Biden administration. I’m inspired by Kathleen Merrigan and her latest report, The Critical To-Do List for Organic Agriculture, which has 46 recommendations for President Biden. I’m looking forward to big policy conversations like that.

I’m also very excited about initiatives that are happening in cities that are showing us a way to urbanize food systems. For example, in Detroit, communities are practicing guerilla gardening in vacant lots and reviving an industrial city that fell on hard times. I’m incredibly inspired by the resurgence of urban agriculture across the country.

What’s your go-to weeknight meal?

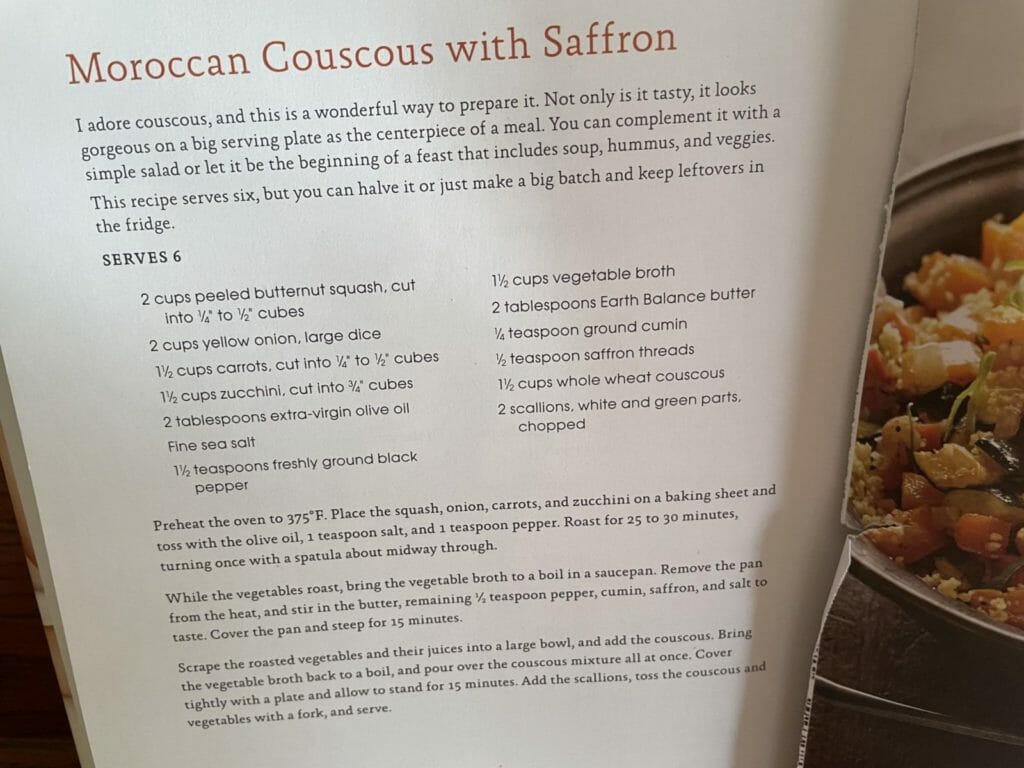

My go-to weeknight meal is Moroccan Couscous with Saffron. I cook it in big batches so that it will last for several weeknight meals. It’s made with hearty winter squash and couscous, and the little pinch of cumin and saffron make it very special. It’s the perfect food to come home to after a long day. The recipe I use is from Alicia Silverstone’s book, The Kind Diet.