By Estève Giraud

I was talking to my friend John, who has been waiting tables for the past 4 years.

“Well, we make do. We have some savings. And I am trying to create an in-house garden. I never thought about this before, but you know, just in case. Plus it feels good.”

John is not the only one. With the current coronavirus crisis, people’s relationship to food appears to be changing.

Most of us alive today have never experienced confinement before. These are unprecedented times which require people throughout the world to operate in uncharted territories. Even though crises are filled with opportunities, they also bring up our fears and vulnerabilities to the surface. The hoarding of food items such as pasta, rice, bread, eggs and meat is a good example of that. People are afraid that they might be lacking food and that the traditional food systems could reach a breaking point either due to labor shortage or demand collapse.

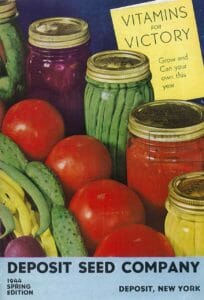

To respond to these fears, an increasing number of people have started growing food, and are calling others to do the same. Seeds sales are booming. In Phoenix, AZ, the Urban Farm started the Victory Garden 2020 challenge in response to the coronavirus. In Albany, New York, the Radix Ecological Sustainability Center is encouraging people to scale-up local food production. And this effort is not limited to the United States. For example, the French organization “Université Francophone de l’Autonomie Alimentaire” has released a call to action to encourage people to start growing food at home and in urban public spaces.

It is not the first time in US modern history that crises push people to the garden, sometimes with government support. During the first world war, the National War Garden Commission encouraged all Americans to create a garden and produce food to support the war effort. Again, in 1933, President Roosevelt’s New Deal heavily subsidized the “Great Depression Relief Gardens” which helped people severely impacted by the economic crisis. Between 1940 and 1945, the War Food Administration created a National Victory Garden program. The United States Department of Agriculture estimates that over 20 million gardens were planted during the Second World War, and produced 44% of the fresh vegetables in the United States. More recently, large urban areas were repurposed during the 2008 economic crisis to produce fresh produce. A few weeks into the COVID-19 pandemic, the idea to reinvent victory gardens seem to be gaining momentum once again. Good news, this is growing season!

Despite this renewing interest, some community gardens are struggling to maintain their activities while respecting social distancing requirements. New forms of cooperation and collaborative efforts are taking place to support food growing activities without spreading the virus. Gardeners are creating virtual spaces such as Facebook groups or using the Nextdoor app to encourage seed, seedling, or mulch sharing, promising to wear gloves and masks during the transactions.

Traditional gardening classes that would normally take place sporadically around urban areas have now shifted online. Growing food classes and tutorials are abundantly spreading all over the internet. They teach how to pick a site depending on the constraints and objectives. For those who have never gardened before, the key is to start small, for instance by simply re-growing an onion or some basil in a cup of water by the windowsill. For more advanced growers, healthy soil can be created anywhere by layering successively green and brown waste such as food scraps, grass cuts, cardboard or dead leaves. It is called lasagna gardening, and it works even on concrete, which is perfect for urban environments.

Kids and college students are also encouraged to make use of their time sheltered-at-home, and to participate. For children, gardening can be particularly fun, as it shows them how to repurpose objects such as yoghurt or egg containers, and they enjoy watching a seed turn into a plant. Beans and lentils are particularly easy for them to grow. Garden experiments can also help them cope with boredom and give them a good occasion to go outside whenever possible.

For college students, gardening can be an opportunity to get outside between online classes and reintegrate into family/home life. Swette Center undergraduate, Jane Coghlan (pictured above), has been spending some of her time at home building several raised garden beds with her parents in their backyard. At ASU Jane is a strong advocate for campus gardens, so her garden has allowed her to continue this passion during this period away from Tempe. Additionally, Jane’s classmates in SFS216: Subsectors of US Food and Agriculture have been eagerly following her gardening journey, illustrating that there is something compelling about watching a plant develop even if only virtually.

In general, gardening is very positive for mental well-being. In these uncertain times, it especially helps release anxiety by connecting with nature. It gives people the opportunity to do something that is both beautiful and useful and provides a sense of security. It is empowering to watch and nurture a plant to grow. When it turns into food that can finally be eaten, it reminds us that with just a little care, we can turn nothing into something.